There's an anecdote in Johann Hari's seminal book, "Lost Connections," where he meets a man named Joe. Joe works in a paint shop. His job is simple: if a customer asks him for a particular shade of paint, Joe takes it to this machine, which shakes the paint vigorously until it is mixed. Then he takes your money and moves on to the next customer. Joe understandably feels like his job makes no difference, and he begins to go into a deep depression.

But Joe has dreams. He loves fishing. He has looked into becoming a fishing guide in Florida. It pays a lot less, but he feels like he would be happy, doing it. He doesn't have kids or a partner, so he has no obligations. So why doesn't Joe got to Florida?

Secretly Joe is still addicted to an idea that seems central to America: that things will make him happy. He says in the book, "if I keep buying more stuff, and I get the Mercedes, and I buy the house with the four garages, people on the outside will think I'm doing good, and then I can will myself into being happy." So Joe stays in his job and his depression deepens.

When Hari walks away from Joe, he calls out to him, "Go to Florida!"

Everyone Hates Their Jobs

A recent Gallup poll asked millions of workers in 142 countries, whether they were engaged with their jobs. 13 percent said they were engaged with their jobs. A staggering 63 percent said they were "not engaged" with their work, while another 24 percent said they were "actively disengaged" from their work. So that means that an amazing 87 percent of workers are disengaged with their work.

I can back up this evidence anecdotally as well. I have about 30 patients in my current practice, and I'd guess a good 80-90% actively dislike their jobs. It has almost become a cliche in our society to not like your job but do it anyway.

So what's going on here? Why are people so unhappy with their work? The answer is complicated, and I don't have all the answers or maybe no answers at all, but I'd like to start with the idea of wage labor.

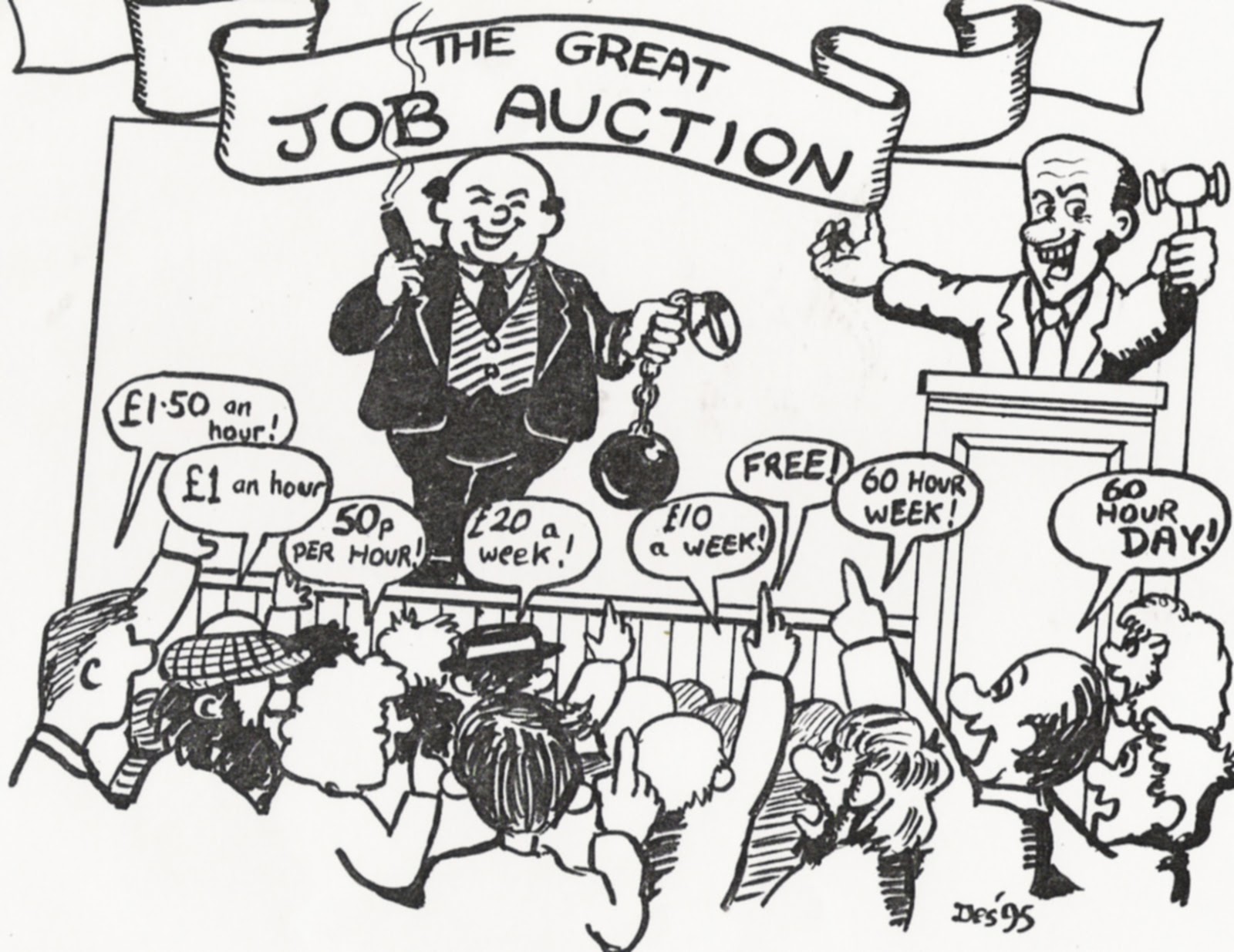

We as a society accept the idea of wage labor, where a laborer sells time or labor power to a company for money, as implicit. But that has not always been the case. In fact in the antebellum period of American history, there were many anticapitalist reformers who compared chattel slavery to wage labor. It was an extreme comparison of course, but even such notable figures such as Emma Goldman denounced wage labor. Goldman once famously said about wage labor, "the only difference is that you are hired slaves instead of block slaves."

Again, I do think the comparison is rather extreme. But it's important to remember that wage labor, which most of us are engaged in, often felt unfree to many people in the 18th and 19th century. The reason? Because wage labor meant people were not in control of their time. You were told where and how long to work for a menial wage so you can barely get by each year. And even if you did well, it was always for someone else so you could buy things to live.

I see that same sentiment in many of my patients. The dislike of their jobs has much to do with the lack of control over their time. I have the sense that most people don't mind working, but it's the number of hours, the politics and the meaninglessness of their tasks that start to wear on them. And that doesn't even account for the commute to and from work. Many of us spend 40-70 hours of our weeks either commuting to our jobs or working at our jobs. It can be soul crushing. It can leave a person constantly anxious. It can lead to depression. And it can seep down into our relationships as well. (I often wondered why so many people drink in New York. I think work is a big part of that!) And often it's at the service of getting things that you don't really need to be happy.

The Universal Basic Income

So what to do about all this? This is a complicated question with a lot of complicated answers. But one solution that gets floated around is the Universal Basic Income (UBI). It's an idea radicals, as well as conservatives have gotten behind for different reasons.

If we were given a wage to take care of our basic needs such as food and shelter, our relationship to wage labor and work could conceivably change our society. Dignity could return to the workforce. The classic cliche of the single mother who is waitressing at a job she hates to make ends meet could be turned on its head. Maybe her boss is terrible to her, but she has to stay otherwise she can't pay the rent. But if UBI ever becomes a reality, maybe she'll have a choice. Maybe she can quit and find other work without the worry that she will lose her apartment. It's a small victory, yes, but it somehow feels more empowering than the majority of legislation in our country told. Isn't this what we all want in the end? A little more control over how we spend our time?